In order to trace the roots of the De La O family who helped settle the area of Doña Ana, New Mexico, the Linealist closely examined the relationship circles of the De La Os of the presidio towns of San Miguel de Cerrogordo (now Villa Hidalgo, Durango) and Guajoquilla (now Jimenez, Chihauhua). As it turns out, each of the De La O circles had a significant connection to the history of New Mexico and/the history of the northern frontier of Nueva España. At times, these circles became inter-connected, indicating that persons from the different circles were actually related to each other. (Please note that many of the cites below are hyperlinked — just press the hyperlinks to view the record.)

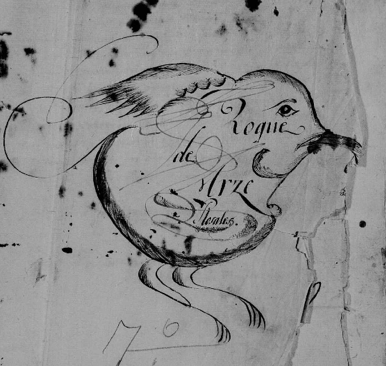

In addition to records from Cerrogordo and Guajoquilla, records from Mapimi, Meoqui, Julimes, Villa de Chihuahua and other towns were reviewed. Every once in a while, something quite pleasant would appear, such as this drawing by a priest in Mapimi, circa 1761.

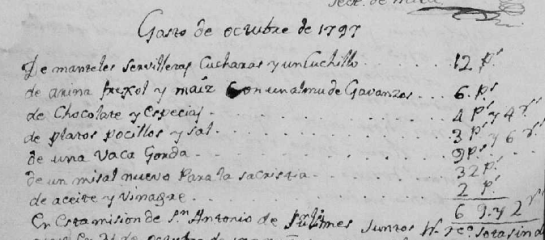

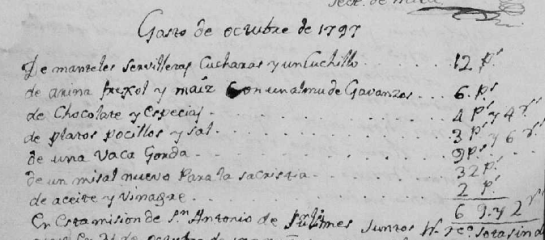

And a priest’s culinary expenses in Julimes in 1797:

Amidst all the turmoil and violence, we can see art and chocolate. (For those interested in the food culture of the northern frontier of Nueva España in the late 1700s, see the Julimes church book at FHL 122290, pp. 80-88.)

Now for Guajoquilla …

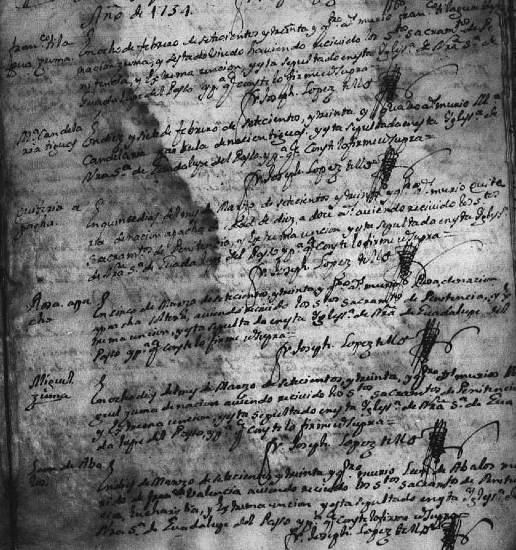

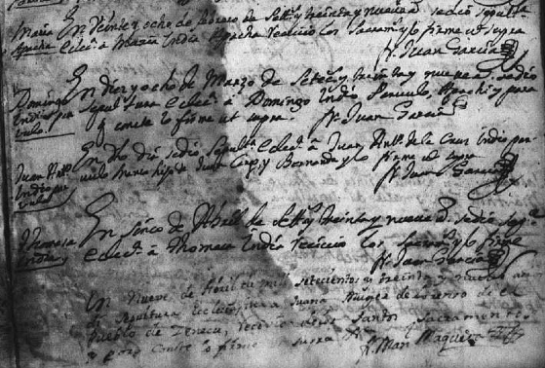

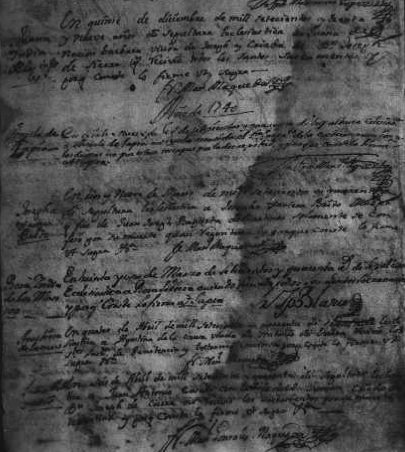

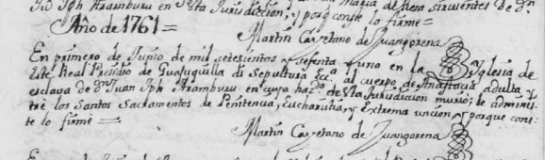

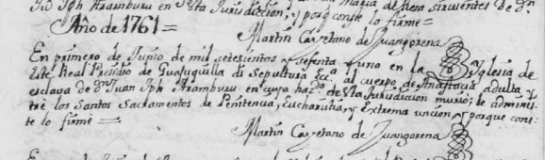

The Presidio town of Guajoquilla was a microcosm of the inequitable society of Nueva España. The top military commanders of Guajoquilla, Juan Joseph Arámburu and Bernardo Antonio Bustamante y Tagle, were ‘peninsular’ Spaniards (born in Spain). Bustamante had previously served in New Mexico. (See e.g., SANM, Span. Arch. 1621-1821, rl. 08, fr. 0773-0779.) Arámburu and Bustamante both enjoyed large salaries and became aristocratic land owners in Guajoquilla. (See Francisco Almada, Resumen Geografico De Municipio de Jimenez, pp. 10-15.) Comparatively, the average soldier was paid little, paid late, and was in heavy debt. (Max Moorhead, The Presidio: Bastion of the Spanish Borderlands, pp. 31-37, 41-46 (University of Oklahoma Press, 1991.) In Guajoquilla, Arámburu and Bustamante purchased haciendas and acquired “mulato” and “Apache” slaves to work on their lands and in their homes. The death records of Guajoquilla from the 1750s to 1760s are filled with the names of Arámburu’s and Bustamante’s slaves and “domesticos.” (FHL 162514). For example, below is the death record for Agustin, described as “apache adulto domestico” of Arámburu. (FHL 162514, p. 9.)

Below is the death record for Anastacia, an adult slave of Arámburu (FHL 162514, p. 13):

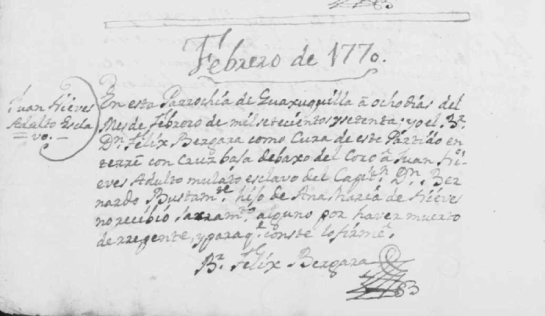

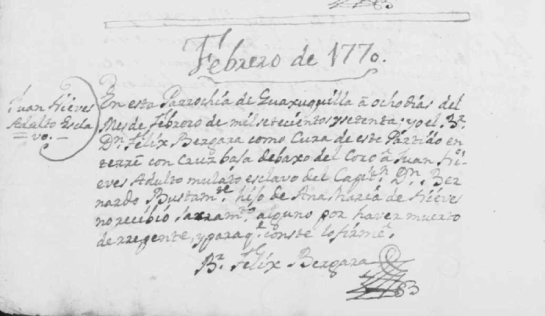

Below is the death record of Juan Nieves, the mulato slave of Bustamante (FHL 162514, p. 44):

The De La Os: Serving the Presidios and the Compañia Volante from Guajoquilla to Santa Fe

Most of the families of Guajoquilla were relatively poor españoles, “mestizos”, “mulatos”, and “indios”, including persons with the de la O surname. As census and muster rolls show, the soldiers of Guajoquilla were accompanied by their families. Like other presidios of the north of Nueva España, the Presidio of Guajoquilla was founded by families of mixed backgrounds, including women and children. Guajoquilla was situated near the Rio Florido and was about five leagues (about 13 miles) from the Pueblo of Atotonilco. (Semanario Económico de Mexico, February 2, 1810, at 34.).

CIRCLE 1. Juan Peres De La O (Juan Jose De La O) and his family, who were some of the ‘original settlers’ of the Guajoquilla, previously lived in the Presidio town of San Miguel de Cerrogordo. In the late 1600s, Cerrogordo was established to protect the nearby hacienda community and the traffic on the road between Durango and Parral. One of the more interesting aspects about Cerrogordo in the 1700s was that, in addition to soldiers and their families and indigenous inhabitants, Cerrogordo had a large “mulato libre” community. (See church records of Cerrogordo inhabitants.) The earliest Cerrogordo record of a De La O that the Linealist has located so far is a listing for a “Joseph de la O” with all his weapons and ten horses in a 1723 muster roll. In the 1700s, individuals with the De La O name in Cerrogordo were mostly described as “mestizo” and a few as “coyote”, “mulato” and “español. Juan Peres De La O was married to Gertrudis Rubio. Their children included Juan Andres (b. 1732, Cerrogordo, FHL 1563292, page 12), Gertrudis (marriage in at FHL 1563292, page 257), and Margarita (b. 1734, Cerrogordo, FHL 1563292, p. 15 ).

Juan Peres De La O and his family moved to Guajoquilla in about 1752 or 1753. (Almada, Resumen Geografico De Municipio de Jimenez, p. 15.) In a 1762 accounting of residents in Guajoquilla, Juan Peres De La O was described as having “todos sus armas, menos cuera, seis caballos, tres yeguas, dos yuntas de bueyes y su familia se compone de cinco personas” — all his weapons, no leather armor jacket, six horses, three mares, two yoke of oxen and his family consisting of five persons). (Id., p. 21.) His son Juan Andres De La O was a soldier who served in the group of first soldiers at Guajoquilla. (Boletin Cronicas de Huejoquilla, p. 5 (Jan 2003).) The soldier Joaquin De La O may have been his son, based on the fact that in 1761 Joaquin served as the padrino for one of Margarita De La O’s children. (FHL 162499, p. 41.)

As discussed in De La O, Part I, Juan Peres De La O’s daughter Margarita De La O was well-regarded in Guajoquilla. She was married to Juan Perú, an Alferez of the Presidio of Guajoquilla as of 1768, who was originally from Paris, France and who became a commander at the Janos Presidio. (Military Roster dated January 4, 1768, from AGN, Provincias Internas, vol. 095, ff. 283-324; catalog TXU, Austin, Lac, Janos F. 004a Sec. 03 pp. 019-094.) Described as “mestisa” in her baptismal certificate, Margarita was usually referred to as “española” in church records when she was an adult. In 1764, her sister Gertrudis De La O married Joseph Antonio Sierra in a chapel at the Zarco hacienda near Cerrogordo; in her marriage record, Gertrudis was referred to as a “servienta en las cruzes.” (FHL 1563292, page 257.) After the death of Sierra, Gertrudis sought permission to marry and likely did marry the military sargeant Jose Antonio Torres of the Presidio de Janos in 1779. (AHAD 30, Item 0657, Diligencia de Gertrudis De La O Rubio (1779); copy obtained from archive at New Mexico State University)

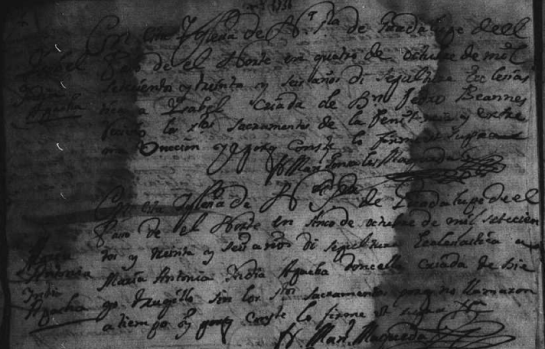

Signature of Gertrudis De La O Rubio

CIRCLE 2. The Joseph de la O and Maria Dias family was also from San Miguel de Cerrogordo. The children of Joseph de la O and Maria Dias included Paulin (b. 1731, FHL 1563292, p. 9), Antonio Joseph (b. 1733, FHL 1563292, p. 13), Juan Mateo (b. 1735, FHL 1563292, p. 20), and possibly Joseph (FHL 162511, p. 28).

There are at least three records that indicate that members of the Joseph de la O/Maria Dias circle were related to the Joseph Peres de la O/Gertrudis Rubio circle. First, in 1772 in Guajoquilla, Margarita de la O and Juan Perú served as the padrinos at the wedding of sargento Joseph de la O and Maria Joseph Salasais. (FHL 162511, p. 28.) This particular Joseph was described as the son of Juan Joseph De La O and Maria Josepha Diaz Marroquin of Cerrogordo. Second, a woman named Gertrudis Rubio (the name of the wife of Joseph Peres de la O) served as the madrina for Antonio Joseph, the son of Joseph de la O and Maria Dias. Third, Gertrudis Rubio served as a madrina for a child alongside a young padrino Paulin de la O (son of Joseph de la O and Maria Dias) in 1747 in Cerrogordo. (FHL 1563292, p. 82.)

Paulin de la O, described as “mestizo” at baptism, married Gertrudis Ronquillo. Paulin de la O and Gertrudis Ronquillo’s children included Chattarina (b. 1765, San Miguel de Cerrogordo, FHL 1563292, p. 176), Francisca Xaviera (FHL 162655, p. 163), Antonio (Sixto Antonio), Josepha, Maria (maybe the same person as Josepha), Pioquinta (FHL Cerrogordo Compilation p. 62), Cristobal Ramon (serving as padrino for child Maria Cornelia, FHL 1563292, p. 630-631), Atanacio (FHL 162500, p. 296; FHL 162511, p. 188-189), and Matheo, who married Luisa Xaquez (FHL 162651, p. 380.)

Paulin served as a padrino at several baptisms and marriages in Cerrogordo. Paulin eventually moved to Guajoquilla, as did some of this children, including Atanacio De La O, who married Magdalena Salcido in 1805. (FHL 162511, p. 188-189.)

CIRCLE 3. Joseph (Jose) De La O and his wife Maria Dolores Estrada, from Cerrogordo, also settled in Guajoquilla. (It is possible that this Maria Dolores Estrada was the second wife of Joseph de la O of the second circle, who had married Maria Dias.) In 1747, Joseph was described as a “cabo de este presidio” (of Cerrogordo) in the baptism records of one of his daughters. (FHL 1563292, p. 82.) Joseph and Dolores’ children included Antonia (b. 1747, FHL 1563292, p. 82), Francisca Xaviera (FHL 1563292, p. 407) and Francisco. Antonia De La O married the military alferez Juan Jose Fernandes, the son of Francisco Fernandes and Maria de la Rosa of the Pueblo de Conchos. (Filacion of Juan Jose Fernandes, Fondo Colonial, Parral Archives.) As of 1789, Antonia De La O and then Sargento Juan Jose Fernandes accompanied troops at the Presidio de San Carlos, which was served by the “Compañia San Carlos de Cerrogordo.” (FHL 162420, p. 19.) Later, Antonia De La O became involved with Ysidro Ojas from Burgos, Spain, who was a Sargent of the Compañia de Volantarios de Cataluña Dragones de España. (See Archivo Historicos de Arzobipado de Durango (AHAD), AHAD-99, Item 0312; 1791 List of Officers and Service Report of the Segunda Compañia Franca de Voluntarios de Cataluña, click HERE; catalog of Archivo General de la Nacion (AGN), Provincios Internas, vol. 83, ff. 092-93 at http://uair.arizona.edu/item/213564.) Antonia and Ysidro sought permission to marry, which involved establishing with the church that Antonia was a widow. (AHAD-99, Item 0312, obtained from NMSU archive.) In 1768, Francisca Xaviera De La O married Joseph Favion de Aragon in Cerrogordo; her father Joseph De La O was dead by this time. (FHL 1563292, p. 407.)

Based on these records, it is evident that some members of the Joseph De La O and Maria Dolores Estrada circle returned to Cerrogordo. But some remained or returned to Guajoquilla, including Joseph’s son, the soldier Francisco De La O. Francisco married Guadalupe Mata and they had at least two children baptized in Guajoquilla in 1818 and 1821, and other children baptized in Meoqui. (FHL 162499, pp. 967 and 1023; FHL 162517.)

CIRCLE 4. Jose Tiburcio De La O was an active member of the Compañia Volante (flying company) regiment based in Guajoquilla. (See Guajoquilla’s Compañia Volante baptism, marriage and death book, FHL 162513). He married Josefa Herrera, who was also referred to as “Josefa Trejo” and “Josefa Salasar” in church records. A baptismal certificate of one of their daughters confirms that Tiburcio was from Cerrogordo. (FHL 162513, p. 14). Although Tiburcio was a member of the Compañia Volante that served in Guajoquilla, he and other members of the Compañia served a significant time at or near other presidios in the ‘northern frontier,’ including Santa Fe.

The Linealist has preliminarily concluded that Tiburcio De La O was the son of Joseph De La O and Dolores Estrada, based on Dolores Estrada’s 1787 death record. The death record says, in relevant part, “Ma [Maria] Dolores Estrada viuda Me [madre] el cavo Tivucio Lao.” (FHL 162513, page 126.)

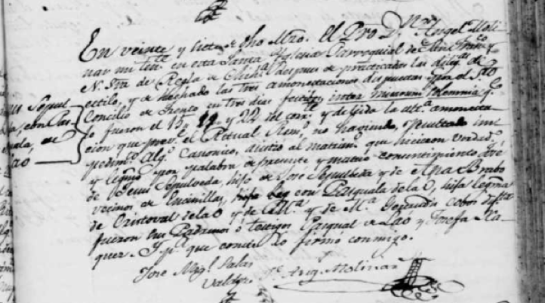

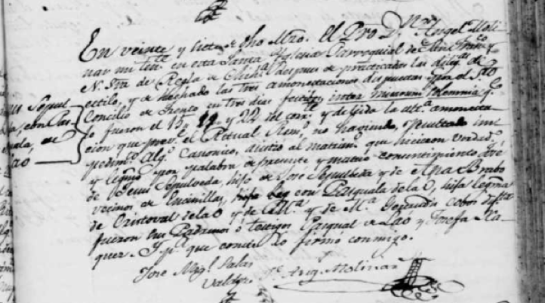

Most of Tiburcio’s daughters married soldiers. In 1795, Soledad De La O married Santiago Abreu, the Alferez of the Presidio of Sante Fe of the Province of New Mexico. Santiago was from Cataluña, Spain. Soledad and Santiago had marriage ceremonies in both Guajoquilla and Chihuahua. (FHL 162513, p. 98; FHL 162691, p. 186.) Soledad’s aunt “Doña Antonia Fernandez” (Antonia De La O) served as madrina at the event in Guajoquilla. According to the baptism record of their child Marcelino, Santiago Abreu was the son of Yayme de Abreu and Francisca de Abreu y Fount. (FHL162666, p. 450.)

Soledad De La O and Santiago Abreu’s son Santiago served as the interim governor of New Mexico in 1832. (See generally, Wikipedia entry.) Their son Ramon reportedly operated one of the first printing presses in New Mexico and distributed a newspaper. (See Anthony Gabriel Melendez, Spanish-Language Newspapers in New Mexico, 1834-1958, p. 17-18.) Former Governor Abreu, and his brothers Ramon and Marcelino were killed during the Chimayo Rebellion of 1837. (See generally, Wikipedia entry. See also, Origins of New Mexico Families, Kindle Loc 5167.)

In 1796 in Guajoquilla, Tiburcio’s daughter Rita De La O married Tomas Amancio, a member of the Compañia Volante. (FHL 162513 p. 101.) Tomas, who was described as an “Indio” in the baptism record of one of their children, became an Alferez of the Third Compañia Volante. ((FHL 162513, p. 51; FHL 162408, p. 305.) In certain years, including 1814 through 1816, Rita and Tomas accompanied the Compañia de San Carlos de Cerrogordo. (FHL 162429, p. 520 and 524.) Rafaela De La O married Jose Maria Zubiran (Subiran). (FHL 162665, p. 457.) Jose Maria Zubiran was the son of the retired military captain Agustin Zubiran of Lorca, Spain and Margarita Beltran del Rio of Villa de Chihuahua. (FHL 162665, p. 608; FHL 162691, p. 44.) Josefa De La O married Francisco Rodriquez. (FHL 162665, p. 460.) In 1809 in Guajoquilla, Dolores De La O married Jose Senteno, and her father Tiburcio was listed as a “sargento retirado” in the marriage record. (FHL 162511, p. 207-208.) (FHL 162408, p. 270.)

In 1795 in Guajoquilla, Tiburcio’s daughter Gertrudis De La O married Martin Yrigoyen (Irigoyen), who was described at the time as a “vecino of Conchos.” (FHL 162511, p. 148.) Gertrudis’ aunt Antonia De La O (“Dona Antonia Fernandez”) and Sargento Ysidro Ojas served as padrinos at their wedding. Santiago Abreu served as one of the witnesses. (Id.) Martin Yrigoyen eventually served as the armorer of the Presidio in Santa Fe, then was reassigned to Cerrogordo, and then served as the “armero de la tropa” near Chihuahua. (Chavez, Origins of New Mexico Families, Kindle Loc 10836; http://uair.arizona.edu/item/223084; FHL 162408, p. 276.) Based on preliminary research, Gertrudis and Martin’s children were born in both Santa Fe and Chihuahua. Their son Jose Maria would serve as the governor of Chihuahua from 1839 to 1840. (See generally, Wikipedia entry.) Their son Antonio Cipriano became a priest and an educator in Chihuahua. (See http://archivohistorico.uach.mx/.)

Tiburcio’s son, Jose (Santiago) De La O, became a soldier. He eventually served as the armorer of the Presidio of Santa Fe, following in the footsteps of his brother in law, Martin Yrigoyen. (See Origins of New Mexican Families, at Kindle LOC 10835-10855.) He married Ana Maria Sena.

Teresa De La O of Guajoquilla was part of the Joseph De La O/Tiburcio De La O circles. Francisco De La O (Joseph’s son and Tiburcio’s brother) served as a padrino at the baptism of one of Teresa’s children in 1789. (FHL 162499, p. 994.) Teresa was married to Joaquin Varela (Barela). (Id.) Teresa’s father was Jose Gervacio De La O. (See FHL 162517.)

Miguel De La O was part of the Joseph De La O/Tiburcio De La O circles based on the fact that he and Soledad De La O served as padrinos at the baptism of the same child in 1791 in Guajoquilla. (FHL 162499, p. 420.) Miguel, a soldier of the Compañia Volante, was married to Soledad Cavesuela. (FHL 162513, p. 98 and 99.) In 1810, Miguel’s son Rumualdo De La O served as a padrino alongside madrina Teresa De La O in 1810. (FHL 162513, p. 72.) Rumualdo was married to Rosa Rivas (FHL 162513, p. 86). A baptism certificate of a child of Rumualdo and Rosa confirms that Rumualdo was the son of Miguel De La O. (FHL 162420, p. 553-554.)

The Linealist plans to write more about the Tiburcio De La O circle, particularly about the sisters Gertrudis De La O and Soledad De La O. Based on a preliminary review of records, many in Tiburcio’s circle and many of his descendants were born and/or lived in New Mexico.

Of the soldiers mentioned above, Ysidro Ojas, Joaquin De La O and Tiburcio De La O are listed in Spain’s Patriots of Northwestern New Spain from South of the U.S. Border in the 1779-1783 War with England During the American Revolution, a copy of which is available by clicking HERE. The De La Os are listed as either “De La O” or “Lao.”

Cristobal De La O: A Teacher Amongst Soldiers

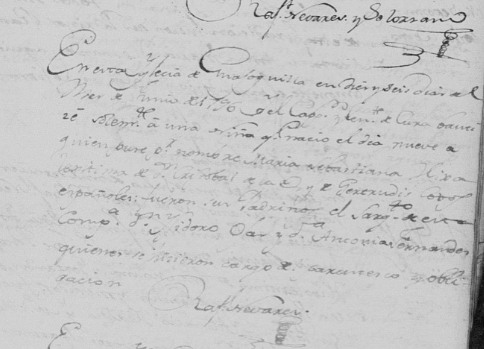

CIRCLE FIVE. The last relationship circle to be discussed is the Cristobal De La O circle. The Linealist has preliminarily concluded that this Cristobal was one of the sons of Paulin de la O and Gertrudis Ronquillo, of the second circle above. This conclusion is based on the fact that Paulin de la O and Gertrudis Ronquillo had a son named Cristobal Roman. Also, Magdalina Salcido, Atanacio De La O’s wife, served as the madrina at Cristobal and Gertrudis De La O son Jose Pablo’s baptism in 1807. (FHL 162499, p. 754-755.).

Cristobal was also likely related to the Antonia de la O, who married Jose Fernandez and then Ysidro Ojas. This conclusion is based on the fact that, in 1796, the padrinos at Cristobal and Gertrudis’s daughter Sebastiana’s baptism were Antonia Fernandez and Ysidro Ojas. (FHL 162499, p. 517.) (As discussed above, Antonia Fernandez was the daughter of Jose Fernandez and Antonia de la O.) This fact suggests that Antonia and Cristobal were related to each other, possibly brother and sister, aunt and nephew, or cousins.

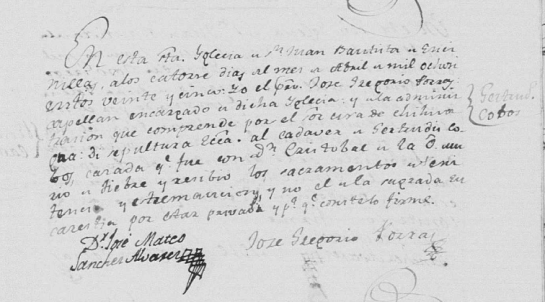

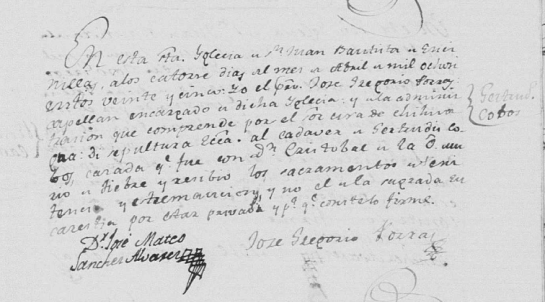

Cristobal de la O was the father and grandfather of the De La Os who helped to settle Doña Ana, New Mexico. In 1791, Cristobal married Gertrudis Cobos (Covos) in Guajoquilla. (FHL 162511, p. 138.) To read about the Cobos family of Guajoquilla, click HERE. Based on a review of records, this Cristobal is likely the son of Paulin de la O and Gertrudis Ronquillo.

In about 1795, Cristobal De La O founded the first primary school in Guajoquilla and became the presidio town’s first teacher. (Francisco Almada, Resumen del Municipio de Jimemez, p. 35.) He became a teacher via military orders, which suggests that he had a military affiliation. In his home or at the home of the military chaplain Rafael Nevares, he taught the children of soldiers and residents of the town how to read, write and count. As Francisco Almada explained:

En el curso de 1795 visitó el presidio militar y la población el expresado Mariscal Nava, quien dejó instrucciones al capitán Garcia de Tejada para que procediera a establecer una escuela de primeras letras, con objecto de que aprendieran a leer, escriber y contar los hijos de los soldados y vecinos. El segundo hizo arreglos con don Cristóbal de la O, quien se obligó a recibir en su casa habitación a los niños de primera enseñanza que se le enviaran, obligándose a impartirles los rudimentos expresados en el término de un año, mediante la paga de tres pesos por cada uno de ellos. La escuela primaria fundada por el professor de la O es la primera de que he encontrado noticias en la actual Ciudad de Jiménez y funcionó en una pieza de la casa habitación del Pbro. Rafael Navárez, que cedió gratuitamente para el objecto y se encontraba unicaba en la calle Hildalgo.

Ibid.

From 1794 to 1814, Cristobal De La O served as a witness at over 65 marriages in Guajoquilla for members of both the main Presidio and the Compañia Volante communities. As for De La O weddings, he served as the testigo at the wedding of Rita De La O and Tomas Amancio (FHL 162513, p. 101), at the wedding of Dolores De La O and Jose Senteno (FHL 162511, p. 207-208), and at the wedding of Atanacio De La O and Magdelina Salcido. (FHL 162511, p. 188-189). He was a testigo at a marriage where Tiburcio’s daughter Gertrudis De La O served as madrina. (FHL 162511, p. 138.) In the record books, he was often times referred to “Xbal Lao.” Cristobal frequently served as testigo alongside the chaplain’s brother, Buenaventura Nevares. Buenaventura was the padrino for Cristobal and Gertrudis’ son, Francisco. (FHL 162499, p. 610.)

Based on Cristobal’s teaching profession and his extensive ceremonial witnessing services, the Linealist speculates that Cristobal was congenial, educated, smart, and likely assigned to protect and assist the military chaplain, Rafael Navares. Cristobal’s parents were likely literate or otherwise knew the importance of education and made sure that Cristobal received an education.

Cristobal and Gertrudis had at least ten children, including:

- Maria Rafaela (born 1793, Guajoquila, FHL 162599, p. 470)

- Maria Sebastiana (born 1796, Guajoquila, FHL 162499. p. 517)

- Jose Nasario Feliz (born 1797, Guajoquilla, FHL 162499, p. 546)

- Francisco De Paula (born 1801, Guajoquilla, FHL 162499, p. 610 )

- Maria Antonia Cesaria (born 1803, Guajoquilla, FHL 162499, p. 655)

- Jose Pablo De Jesus (born 1807, Guajoquilla, FHL 162499, p. 754-755)

- Jose Anselmo Pasqual (born 1809, Guajoquilla, FHL 162499, p. 800)

- Romano

- Pasquala

- Anastacia

Most, if not all of, Cristobal’s and Gertrudis’s children were baptized at Guajoquilla. (FHL microfilm 162499). The baptismal records do not reflect the names of grandparents, unfortunately. As discussed above, Sebastiana’s padrinos were sargeant Sargento Ysidro Ojas and Antonia De La O. The soldier Francisco Covos (possibly our Gertrudis’s brother) was the padrino for Nasario. (FHL 162499, p. 546.) Please note that Chaplain Rafael Nevares seems to have confused Cristobal De La O and Gertrudis Cobos with the Guajoquilla couple Paulin De La O and Gertrudis Melendes in Rafaela’s baptism certificate. (FHL 162499, p. 470; FHL 162514, p. 252.)

At this writing, the baptism records for Pasquala, Romano or Anastacia have not been located. It is possible that one of these records may, if located, show the names of the parents of Cristobal and Gertrudis. (Pasquala, Anastacia and Romano appear in other records, which is how we know of their existence.) It is possible that Pasquala, Romano or Anastacia were adopted.

The Mexican War of Independence started in about 1814 and lasted until 1821 and beyond. During the turmoil of war, at some point before or in 1819, Cristobal De La O and Gertrudis Cobos moved their family to San Juan Bautista de Encinillas. Encinillas was a ranching and farming community about 150 miles northwest of Guajoquilla and near the Villa de Chihuahua. Encinillas also had an abraje (textile factory), where workers toiled long hours and some served criminal sentences of hard labor, up until the early nineteenth century. (Cheryl English Martin, Governance and Society in Colonial Mexico: Chihuahua in the Eighteenth Century, p. 193 (Stanford University Press 1996).) Encinillas records reflect the names of Cristobal, Gertrudis and their children Francisco, (Pablo) Jesus, Pasquala, Pascual, Maria, and Anastacia.

In 1818, Cristobal’s and Gertrudis’s daughter Maria Rafaela De La O married the “Indio” Martin de la Cruz, the son of Gabriel and Nasaria De La Cruz, in Julimes, Chihuahua, about 100 miles north of Guajoquilla. Maria Rafaela was described as an “española natural” from Guajoquilla. Julimes was a military town at the time. A Presidio had been established in Julimes in 1777.

In Encinillas, the De La O family experienced joy and heartbreak. Cristobal served as a frequent testigo at weddings at the hacienda’s chapel and likely continued to teach. One of his and Gertrudis’ daughters, described generally by the priest as “Maria De La O,” had four children: Vidal in 1820; Quilano (Aquilano) in 1823; Pascuala Prudencia in 1825; and Pascual Roman in 1827. (FHL 162407, pp. 423, 443, 459, 470.) She apparently named a few of her children after her siblings, Pasqual, Pasquala and Roman. Jose Vidal and Aquilino died as babies. (FHL 162498, pp. 60, 65.) (This Maria De La O may be Sebastiana or another De La O daughter.)

In 1821, Antonia De La O married Blas Rivera (Encinillas Marriage Book, p. 51). Blas was the son of Joseph Maria Rivera and Maria Josefa Hernandez of Chihuahua. (FHL 162644, pp. 64-65.) The next year, Antonia and Blas had their first child, Julio Demetrio. (FHL 162407, p. 435-436.)

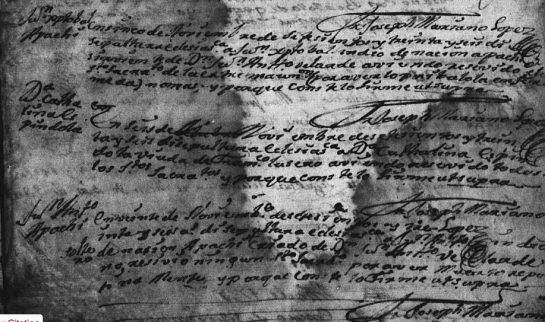

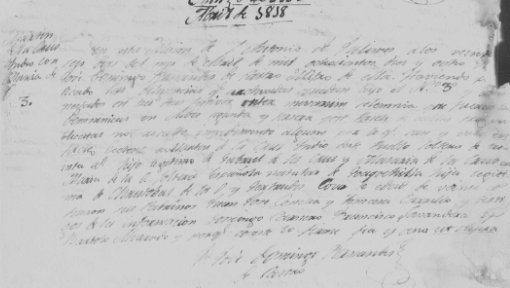

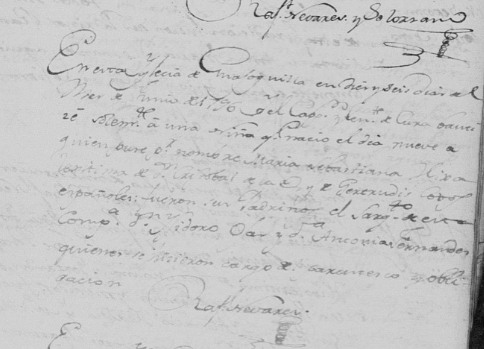

In 1825, the family matriarch Gertrudis Cobos got sick and died of a fever. Her death must have been a shock to the family. One of her youngest children, Pascual, was only about 16 years old at the time. Below is Gertrudis’ death record:

By 1827, Cristobal De La O returned to Guajoquilla to accept a teaching position at the primary school in the small town. However, the teaching conditions were unacceptable. He formally complained to local authorities about the poor teaching facilities and the problem of student attendance. Eighty-five students were enrolled but only forty-nine attended. Cristobal demanded the names of the parents whose children were not attending. (Guillermo Cervantes, La Villa Jimenez, Borderlands Studies Publishing House, 2009, Kindle location 762-774.) At the time, it appears that Cristobal’s young adult children remained in Encinillas and occasionally took trips to Chihuahua for wedding ceremonies.

In Chihuahua, the ornate cathedral San Francisco de Asis y Nuestra de Regla (Our Lady of Rule) was finally completed in 1826, having taken about 100 years to build.

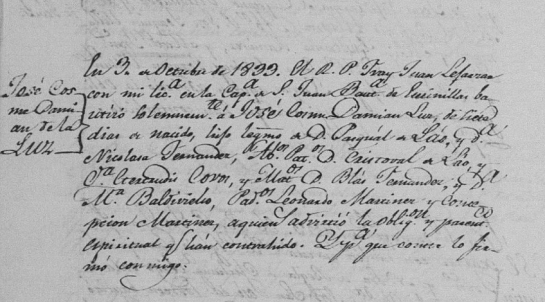

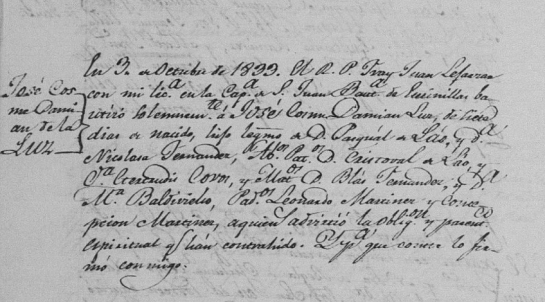

In 1829, at the Chihuahua cathedral, Pasquala De La O married Jesus Sepulveda, the son of Jose Sepulveda and Ana Brabo of Encinillas. (FHL 162692, p. 242.) Her brother Pascual was the padrino at the wedding.

In 1832, Pasquala De La O and Jesus Sepulveda had their daughter Maria Dolores Josefa Pasquala de Jesus, who was baptized in Encinillas. (FHL 162407, p. 497.) The same year, Anastasia De La O married Ramon Montenegro (Paz) in Encinillas. (Encinillas Marriage Book, p. 70.)

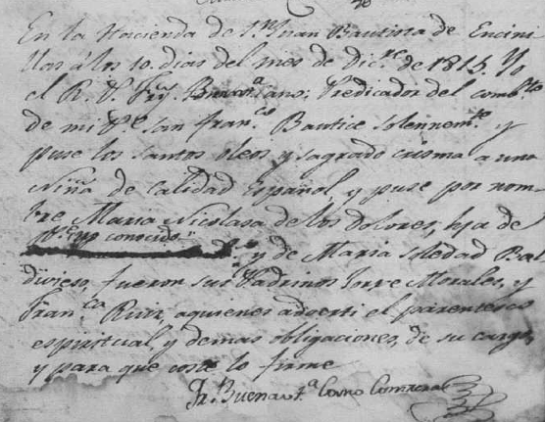

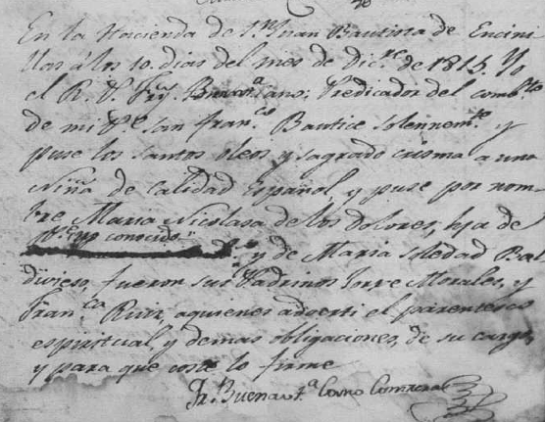

Also in 1832, Pascual De La O married Nicolasa Fernandez Baldivierro at the cathedral of San Francisco de Asis y Nuestra de Regla in Chihuahua. According to her 1815 baptism record, Nicolasa was a “niña calidad español” of Maria Soledad Baldiviero. In her baptism record, the priest crossed out the name of the father and replaced it with the phrase “no conocido.” (FHL 162407, p. 121.)

Pascual and Nicolasa’s marriage record describes Nicolasa as having been put in the home of Soledad Baldiviero. Pasqual’s sister Anastacia served as the madrina at their wedding. (FHL 162692, p. 300.)

On the baptism certificates of Pascual and Nicolasa’s children, however, the maternal grandparents are listed as Blas Fernandez and Soledad Baldivierro. Based on a review of Encinillas church records, the Linealist has concluded that “Don Blas Fernandez” or “Don Juan Blas Fernandez,” as he was referred to, may have been married to another woman (not Soledad) when Nicolasa was born. Both the Fernandez and the Baldivierro families were established in Encinillas before Cristobal and Gertrudis arrived there. In 1817, Blas Fernandez wrote a letter to Archdiocese authorities complaining about the lack of a chaplain for the Hacienda at Encinillas, which created hardship due to the distance of the nearby Villa (Chihuahua). He requested a chaplain on behalf of the “genteel” residents of Encinillas. (AHAD 233, Item 0581.)

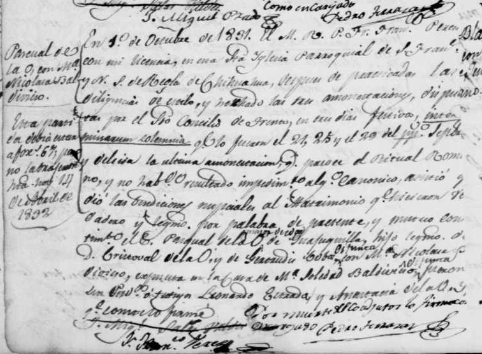

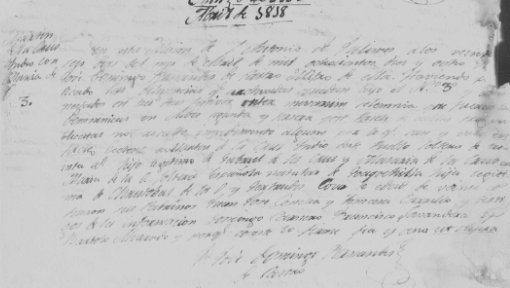

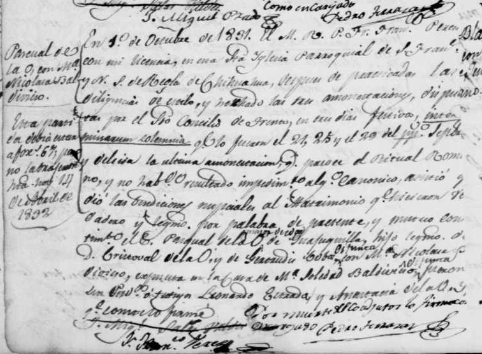

Pasqual’s and Nicolasa’s first child, Cosme De La O, was baptised in Encinillas in October 1833. (FHL 162407, p. 503.) Below is Cosme’s baptism record, which lists Cristobal De La O and Getrudis Cobos as his paternal grandparents and Blas Fernandez and Maria (Soledad) Baldiviero as his maternal grandparents.

Also in October 1933, Anastacia and her husband Ramon had a daughter named Maria Francisca Placida de La Luz. (FHL 162407, p. 503.)

In the early 1830s, Cristobal moved to the small town of Santa Ysabel. In 1832, the year of both his children Pasqual’s and Anastacia’s weddings and during a period when his grandchildren were being born, Cristobal De La O was the target of the ire of wealthy landowners of the very small town Santa Ysabel (later called General Trias), about 80 miles south of Encinillas. (Carmen Casteñeda Garcia, et al, Lecturas y lectores en la historia de Mexico, pp. 80-81 (2004).) In Santa Ysabel, where he apparently moved, Cristobal taught from the book, Catecismo de Republica o elementos del gobierno republicano popular federal de la Nacion Mexicana by the author Anselmo Maria Vargas and published by Martin Rivera.

Catecismo de Republica, a 28-page book, provided lessons in the basic concepts of a democratic government for students in Mexico after the Independence from Spain. In question and response form, the book taught the difference between an aristocratic government and a democratic government. It explained that the former government, before the Mexican Independence, was an unfair government run by monarchists.

Wealthy landowners in Santa Ysabel wrote a letter to authorities complaining that Cristobal De La O, through his teaching, was inciting rebellion and siding with the indigenous. (Lecturas y Lectores en la historia de Mexico, pp. 80-81, n. 21 [citing letter in the Archivo Municipal de Chihuahua].) The short preface for the book Catecismo de Republica, from which Cristobal De La O taught, said “Combatid la ignorancia y desaparacerá la eslavitud.”

Fight ignorance and servitude will vanish.

As the authors of Lecturas y Lecturas explained, it was not only significant that Cristobal De La O and other teachers like him expressed themselves in rural and remote lands, but that they dared to raise their voices against the wealthy and powerful. Based on this, we can assume that Cristobal was a man who cared deeply about democratic ideals. He was strong, bold and intelligent – a teacher and a fighter.

Some of Cristobal De La O and Gertrudis Cobos’ children would settle in Senecú then Doña Ana, New Mexico. Their son Pascual would become an advocate for the many poor Senecú families who made the request to establish Doña Ana. Their grandson, Buenaventura, would become one of the first teachers (maybe the first teacher) of Doña Ana. Many of their grandchildren and great-grandchildren would become musicians in New Mexico. Read the forthcoming, De La O, Part 3, which will be posted in 2014.